Pregnant women eagerly anticipate their due date, but only 5% of births actually occur on the estimated delivery date. Labor typically starts two weeks before or after the due date, but there are no reliable ways to determine when that will be.

A recent study published in Nature Partner Journals Digital Medicine was conducted by Elise Erickson, PhD, CNM, FACNM, Assistant Professor at the University of Arizona and Neta Gotlieb, PhD, Product Manager and former Lead Research Scientist at Oura, along with their colleagues, sought to understand whether a health wearable like Oura Ring could help predict labor onset.

Using machine learning, the research team was able to discover a pattern between physiological data points and the forecasted length of pregnancy in relation to their due date.

Read the full study here.

The “Due Date” Fallacy

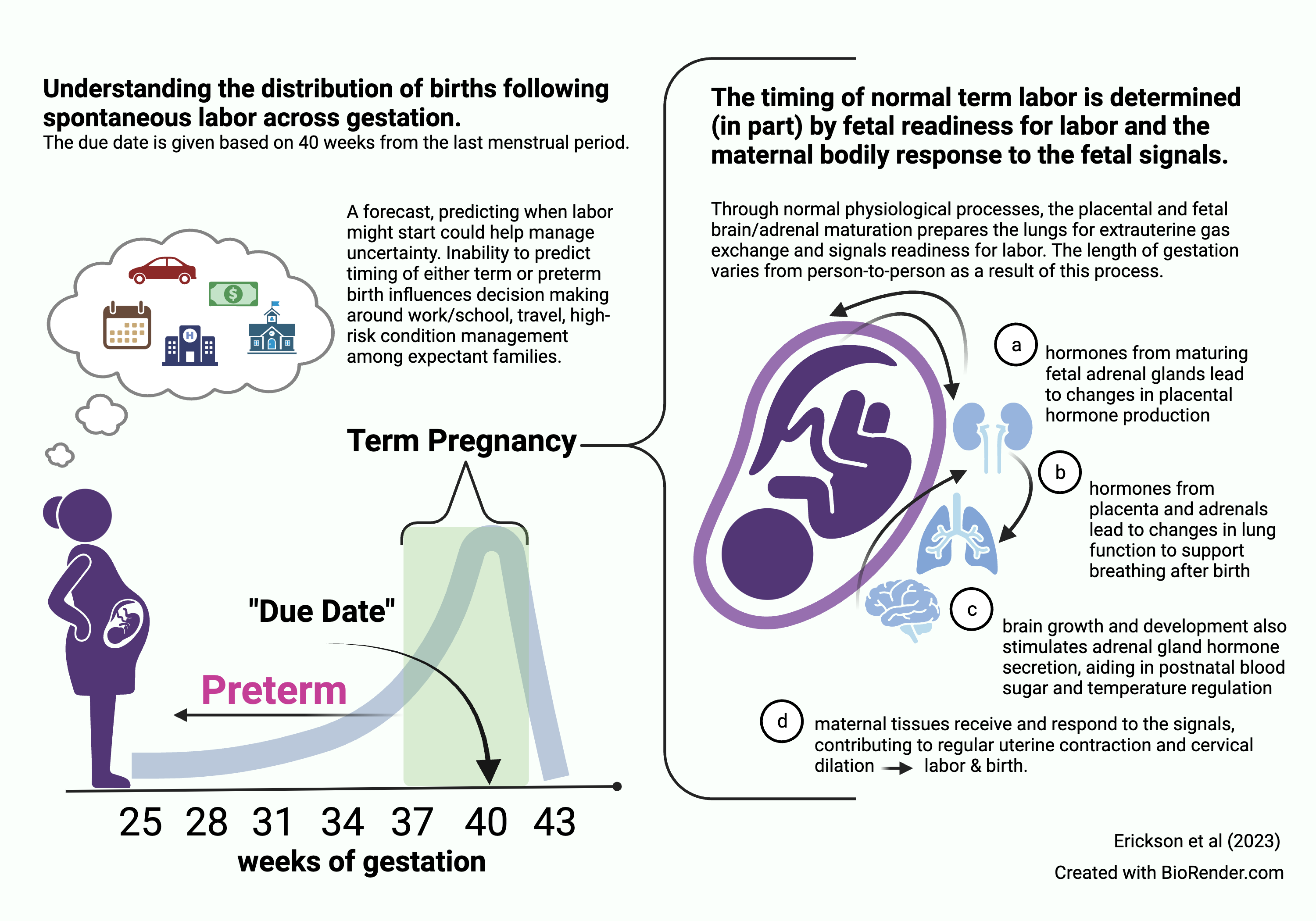

At the start of a pregnancy, women are given a “due date” when their baby is expected to be born. This clinical estimated delivery date (EDD) is based on the first day of the last menstrual period plus 280 days (40 weeks), and assumes a 28-day cycle with ovulation occurring on day 14.

However, most menstrual cycles are not 28 days long and ovulation doesn’t always occur on cycle day 14. Just like an average cycle length is used (28 days) over a personal one, an average gestational length is used to calculate one’s EDD. In practice, gestational length varies. More than 90% of babies are born two weeks on either side of the EDD; however, less than one in 20 babies (about 5%) are born on their due date.

“Pregnant individuals and their families often seek greater clarity from their doctors and midwives on when exactly they will give birth,” study researcher Gotlieb explains. This can be due to an array of reasons, ranging from the stress around uncertainty, needing to plan around work commitments (especially where there’s limited maternal medical leave), or arrange care for family members during labor and recovery, to having to travel far to a hospital that provides obstetrics care or high-risk pregnancies that cannot undergo natural labor.

This was the case for Gotlieb, who tells us:

“When I was pregnant with my second child, the question of my delivery date carried significant implications. I had a high-risk pregnancy and no one knew how long my body would be able to support it. Being able to estimate that timeline would have allowed my care providers and me to weigh the risks and inform critical decisions. I asked my doctor to put our brains together to predict when I’d go into labor. I was certain that between her and myself, an OBGYN and a reproductive scientist, we’d be able to tackle that question. But medicine rarely offers such personalized solutions.”

Erickson’s 18 years of experience caring for expectant families as a Certified Nurse Midwife, as well as a mother of two babies who passed their “due dates,” led her to explore the connection between physiological signals and labor onset as a way to help improve both family experiences and clinical decision-making. As Erickson says:

“Every pregnancy has its own unique timeline in terms of when the placenta, baby’s body and mother’s body work together to prepare for labor and give birth. This study was inspired by several animal studies showing that labor could be predicted by paying close attention to maternal physiological changes. Having a better forecast for each person’s timeline would revolutionize the concept of the due date for the first time and really transform our ability to provide the best possible care to each person.”

Figure 1: Distribution of labor and birth in human populations and fetal maturation leading to labor onset.

Study Design

The study enrolled 118 women in the third trimester of their pregnancy. They were asked to continuously wear an Oura Ring, and underwent weekly assessments to monitor any physical or emotional changes related to their pregnancy.

Using a 3D accelerometer, body temperature sensor, and infrared photoplethysmography sensors, Oura measured participants’ heart rate, heart rate variability, skin temperature, sleep, and physical activity. Additionally, participants completed a weekly survey to assess any labor symptoms they may be experiencing, as well as their pain level, fatigue, and overall mood.

Once the participants gave birth, they were asked to report the timing of their labor, whether they were induced, had a Cesarean birth, as well as other postpartum specificities.

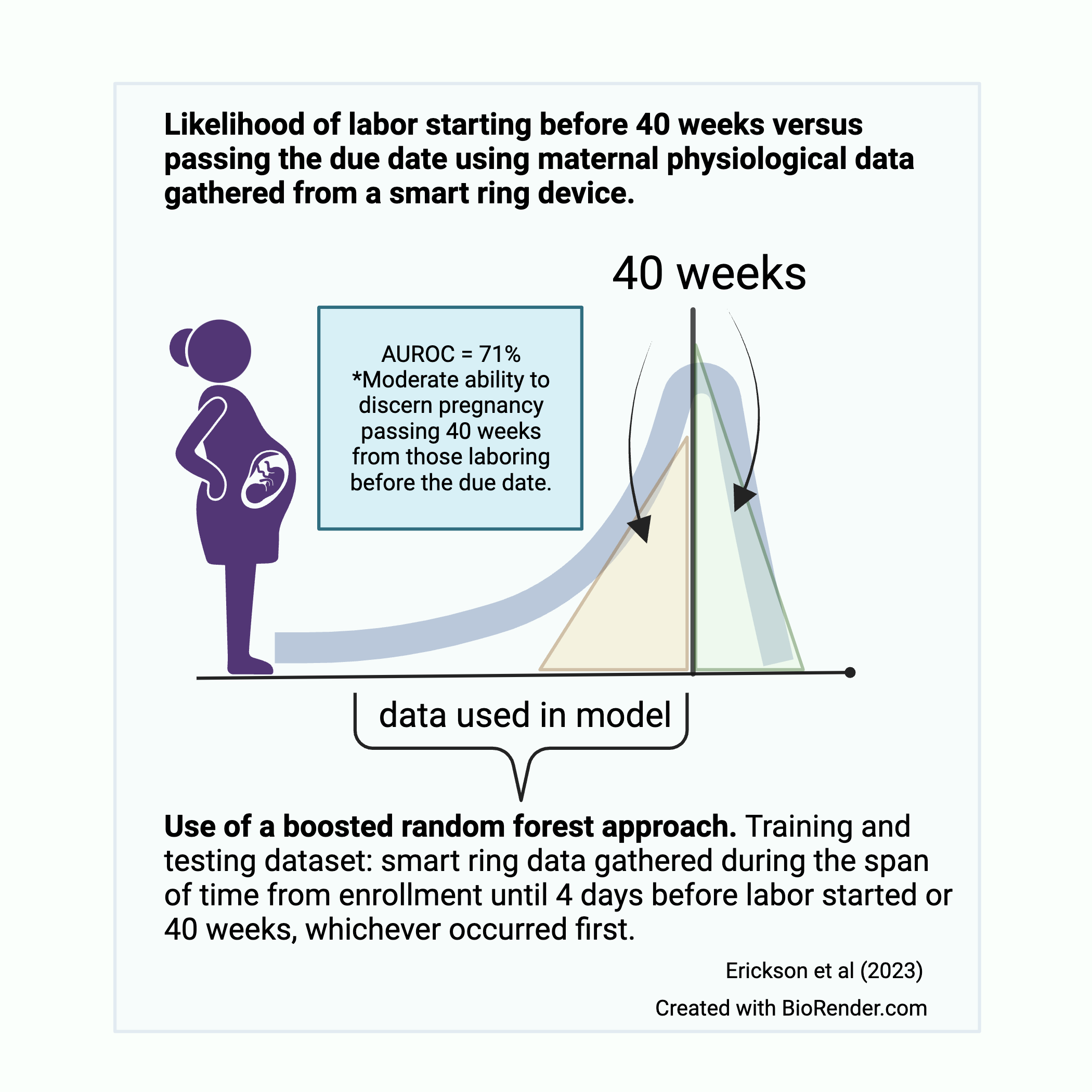

Using a machine learning approach, the daily averages of 30 Oura metrics were used to train a mode. The analysis sought to predict which biomarkers related to “early” or “late” births, in relation to the EDD.

LEARN MORE: Technology in the Oura Ring

Key Findings

- Oura Ring metrics, specifically skin temperature, metabolic activity, physical activity levels, and sleep patterns, were useful in predicting labor onset with 71% accuracy.

- Gestational age alone was only 58% accurate, which is only slightly more accurate than flipping a coin.

- Interestingly, clinical characteristics (maternal age, number of prior births, body mass index) and symptoms (contractions, vaginal discharge, or back pain) that are commonly used by doctors as indications of labor, had no predictive value.

Figure 2: Metrics for evaluating the model performance using smart ring data.

A “Major Step Forward”

Women’s reproductive health has been historically under-researched. Oura’s ongoing commitment to this field, combined with our advanced health-tracking technology, is contributing to an enhanced understanding of women’s reproductive health.

While 71% accuracy is better than the current 58% accuracy of due dates, it has not yet reached clinical application. Nonetheless, the findings provide a foundation for future clinical testing. The continuous advancement of Oura’s technology is marking new exciting developments for women – being able to better predict birth offers women greater autonomy and comfort in relation to their reproductive health.

Read the full study here.

READ MORE: Oura’s Commitment to Prioritizing Women’s Health

About the Oura Experts

Neta Gotlieb, PhD, is a Product Manager and former Lead Clinical Research Scientist at ŌURA researching and developing solutions focused on women’s health. Dr. Gotlieb received her Master’s degree from Tel Aviv University in Biological Psychology where her work focused on how stress impacts immune function and endocrine pathways. She earned a PhD from UC Berkeley where she studied Reproductive Neuroendocrinology and the circadian regulation of menstrual cycles, pregnancy, and birth. Recipient of the Women in Tech Global Technology Leadership Award and Women of Wearables’ Trailblazing Leaders in Women’s Health and FemTech.

Elise Erickson, PhD, CNM, is an Assistant Professor and Certified Nurse Midwife at the University of Arizona College of Nursing jointly appointed in Obstetrics and Gynecology. She has been a midwife since 2005, earning a Master’s degree from the University of Illinois Chicago. Her PhD was completed in 2018 from Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) where she served as a faculty member from 2014-2022, teaching perinatal physiology and leading maternal health research. Her current work is funded by the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute for Nursing Research, Tech Launch Arizona, University of Arizona-Research Impact and Innovation Award. The present study was supported in part by the Oregon Clinical Translational Research Institute-Biomedical Innovations Program, The OHSU School of Nursing Foundation and The American College of Nurse-Midwives Foundation.