Written By: James Hewitt

Take a moment, and imagine if sleep was energy we could deposit in a bank.

Conventionally, adult humans are “monophasic sleepers,” which means they sleep in a single block, depositing sleep as one payment each night. However, some individuals have tried “polyphasic sleeping,” where sleep is divided up throughout the day in a series of smaller sleep segments of a few hours scattered throughout the day. At first, it’s tempting to think that, as long as the numbers add up, your sleep account balance would remain healthy in either situation.

However, even though 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 = 8, the math doesn’t add up when it comes to sleep. 8 hours in a single deposit is completely different from 2-hour bursts over time. While a polyphasic schedule may keep you just above the sleep poverty line, it is not an optimal strategy for health or performance.

Why Do People Try Polyphasic Sleep?

Many people are under increasing pressure to achieve more in less time, so what is the first thing that’s cut out in the pursuit of maximum productivity? Sleep. The principle of the eight-hour work day was established in 1919, but 100 years later, 65% of people continue to work more than 40 hours per week.

The search for more wakeful hours has led some people to experiment with polyphasic sleep schedules. Proponents suggest that it’s possible to adapt to a polyphasic schedule, significantly reducing total sleep time, while maintaining high levels of performance. Polyphasic sleep is widespread in the animal kingdom, human babies sleep polyphasically for the first year after birth, and there are several examples of high performers adopting polyphasic sleep schedules. So, could proponents of this sleep method be correct?

Learning From Round-the-World Sailing Competitions

Thousands of shift workers are constantly balancing their sleep and schedules to maximize their performances, but there is also a unique sport that involves a similar sleep-performance balancing act. Single-handed (solo) yacht races create a unique set of demands, requiring a delicate balance between cognitive and motor skills, sustained for weeks on end, in unpredictable conditions.

Even when visibility is normal, sailors should check the horizon at least once every 15 minutes, to prevent collisions. Anytime a solo sailor is asleep, they are at risk.

The Most Successful Competitors Slept Less

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a study of 99 sailors competing in solo ocean sailing events revealed a significant relationship between sleep and race performance — the most successful competitors slept less, generally for periods between 20 minutes and one hour, for a total of 4.5 to 5.5 hours of sleep per day.

However, while polyphasic sleep may be a good strategy for surviving on the high-seas, the evidence indicates that it’s not well suited for long-term health or performance.

Polyphasic Sleep Destroys Sleep Cycles

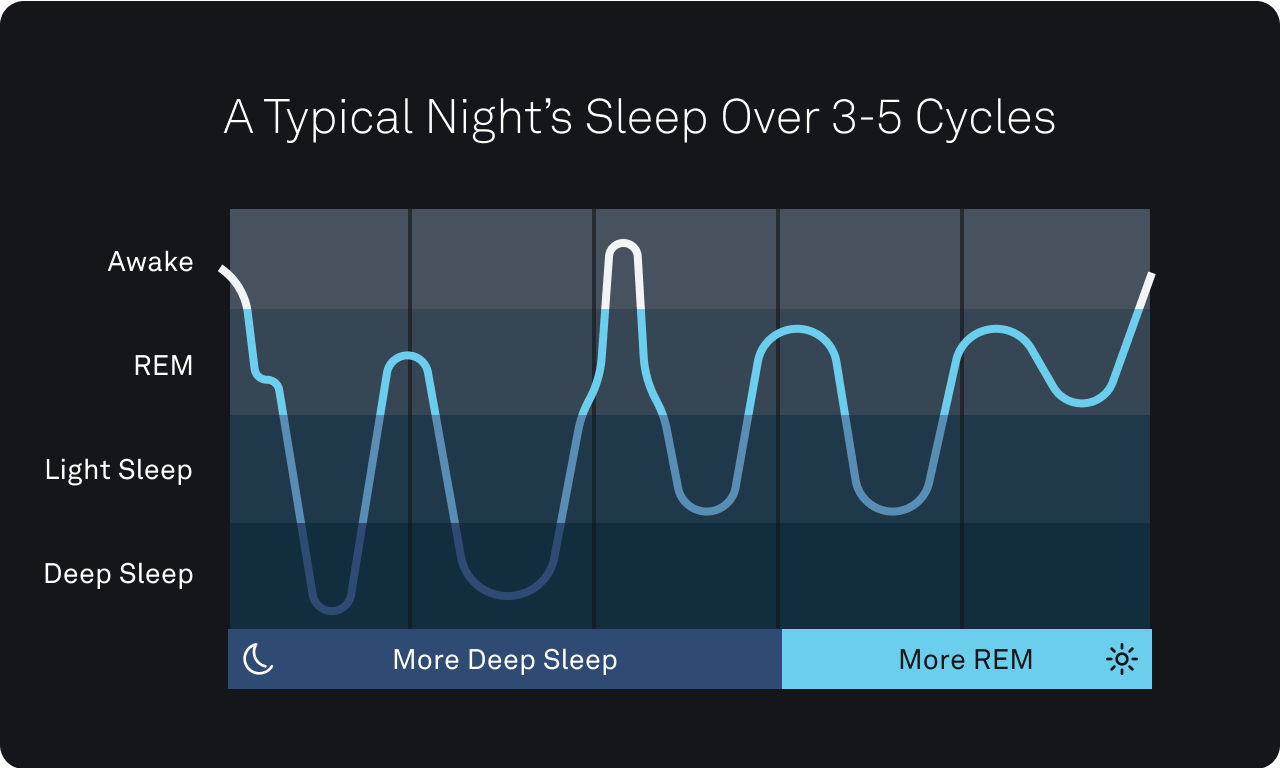

Sleep has been traditionally divided into 4 categories: awake, light, deep, and REM sleep. We experience higher levels of deep sleep in earlier cycles, then increasing amounts of REM sleep in later cycles.

However, if you sleep in polyphasic ‘shifts,’ sleep cycles are separated and shortened, and the normal transitions between sleep stages are disrupted. This disruption can impair cognitive performance, particularly concerning learning and memory, with the adverse effects persisting for several days.

We Can Sleep Polyphasically, But There is a Cost

Some studies indicate that it is possible to adapt to a polyphasic schedule and minimize some of the downsides. However, participants in these studies followed a structured sleep schedule, and only then for relatively brief, intense periods motivated by survival or competition.

In contrast, most people who try to assemble sleep time from irregularly sized chunks end up living in a continual state of body-clock disruption, harming metabolic health and decreasing cognitive performance. Routinely sleeping for less than 7 hours is also associated with increased injury risk, compromised immune system function, and reduced bone density in some populations.

Sleep is an Investment

We can’t treat sleep like a bank account. Sleeping four hours in one chunk, then three hours in another is not equal to seven hours of continuous sleep, and, when we don’t sleep enough, we accumulate sleep debt at a very high interest rate. Except for in a few extreme scenarios, polyphasic sleep does not make sense. Nothing beats a single 7+ hour block of sleep; it is one of the best investments you can make for sustainable high performance.

Author Bio

James Hewitt is a performance scientist and award-winning communicator. He has dedicated his career to enabling people to perform at their best through sharing novel data, cutting-edge insights, and practical tools, developed in his work with the world’s most demanding & top-performing organizations.

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (2019) Usual hours worked by weekly hour bands in OECD countries [online] Retrieved 12-22-2020; https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=AVE_HRS

- Stampi C. Polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance: A field study on 99 sailors. Work Stress. 1989;3(1):41–55.

- Lockley, S. & Foster, R. (2020) Sleep: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

- Kuiken, D. Dream Function. In: Squire L.R, editor. Encyclopedia of Neuroscience. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2009. p. 639-645.

- Claudio S. The Effects of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep Schedules. In: Stampi C, editor. Why we nap. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 1992. p. 137–79.

- Broussard JL, Ehrmann DA, Van Cauter E, Tasali E, Brady MJ. Impaired insulin signaling in human adipocytes after experimental sleep restriction: A randomized, crossover study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(8):549–57.

- Shi SQ, Ansari TS, McGuinness OP, Wasserman DH, Johnson CH. Circadian disruption leads to insulin resistance and obesity. Curr Biol. 2013;23(5):372–81.

- Sio UN, Monaghan P, Ormerod T. Sleep on it, but only if it is difficult: Effects of sleep on problem solving. Mem Cogn. 2013;41(2):159–66.

- Johnston R, Cahalan R, Bonnett L, Maguire M, Glasgow P, Madigan S, et al. General health complaints and sleep associated with new injury within an endurance sporting population: A prospective study. J Sci Med Sport [Internet]. 2020;23(3):252–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2019.10.013

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol. 2012;463(1):121–37.

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Hovey KM, Andrews C, Cauley JA, Hale L, Li W, et al. Short Sleep Is Associated With Low Bone Mineral Density and Osteoporosis in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Bone Miner Res. 2020;35(2):261–8.