Sleep wearables are becoming increasingly popular, but how does the average consumer decide which one to buy? Accuracy and performance certainly play a role in the decision-making process and have become increasingly important as more and more consumer sleep trackers enter the market.

“A growing consumer demand for high accuracy has led to a profusion of ‘validation’ studies in the last 5 years,” notes Dr. Michael Chee, MBBS, FRCP (Edin), director at the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Sleep and Cognition and Oura advisor.

“However, with a few notable exceptions, most studies have tended to evaluate mostly younger adults, in relatively small samples (~20), and have not systematically demonstrated the value of higher-quality consumer sleep trackers in head-to-head comparisons.”

To address these gaps in knowledge, the Centre for Sleep and Cognition at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, recently reported on the concurrent evaluation of different classes of devices: a well-respected portable electroencephalogram (EEG) headband; two well-respected consumer sleep trackers; one a ring, another a wristband, a research ActiGraph, and two low-cost wrist-band sleep trackers. Older and younger adults were tested. The team used state-of-the-art performance evaluation measures.

Oura emerged as the top non-EEG-based device.

READ MORE: Oura Data Validated Against Sleep Lab Gold Standard

Study Design

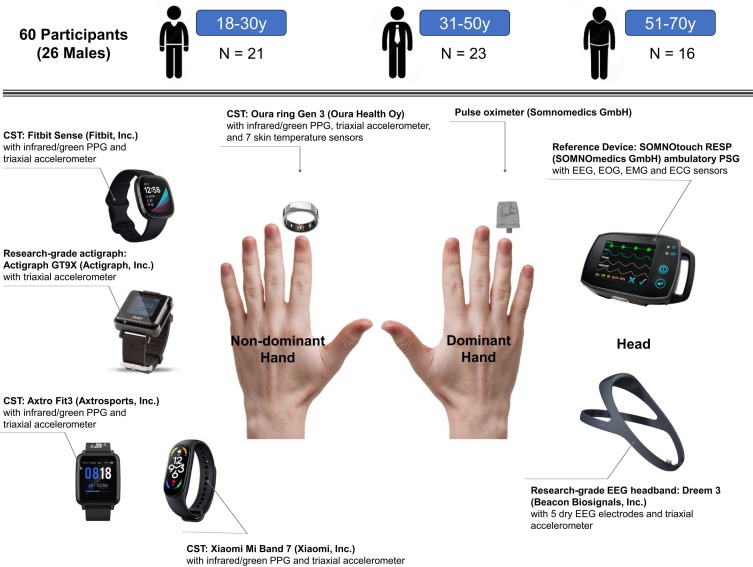

The study evaluated sixty participants, comprising 26 males and 34 females, across 3 age groups (18-30, 31-50, and 51-70 years). The participants were healthy and did not have any pre-existing sleep, neurological, or psychiatric disorders.

Participants slept overnight in a sleep laboratory while connected to polysomnography and wearing five wearable devices. The research actigraph used was the ActiGraph GTX9, and other devices included the Dream-3 EEG-based headband, Oura Ring Gen3, FitBit Sense, and two low-cost devices (Xiaomi Mi Band 7 and Axtro Fit3 band) which were worn by alternate participants.

The study was conducted with careful adherence to the latest guidelines on the testing of consumer sleep trackers. The team examined how well sleep and wake could be differentiated, separately from how well the different devices could stage participants’ sleep. Special attention was paid to measures that distinguish higher-performing from lower-performing devices — these were ‘specificity’ and ‘kappa statistic.’

Key Findings

- Not surprisingly, the EEG headband was the best-performing wearable device.

- Among non-EEG-based wearables, there was a clear distinction between the performance of high-quality devices and their low-cost counterparts.

- Oura performed the best overall both for sleep and wake detection as well as sleep staging.

- The devices were more accurate when measuring the sleep of good sleepers (with PSG-determined sleep efficiencies of more than 85%) than sleepers with lower sleep efficiency. Note that older adults generally have less efficient sleep than healthy younger ones.

- The two high-quality devices both outperformed actigraphy.

Discussion of Findings

The findings provide evidence-supported guidance about how to select a sleep tracker fit for purpose, Chee notes. For clinical trials where the highest accuracy is needed, the tested EEG headband is recommended. For the vast majority of other users who do not have significant sleep difficulty and just want to monitor their sleep with good accuracy, a higher-quality consumer sleep tracker is recommended.

One consideration: Device performance can be affected by sleep efficiency, so data may be less accurate for individuals with very disturbed sleep or a sleep disorder, Chee adds.

“This work contributes to the growing literature demonstrating that a quality ‘consumer’ sleep tracker can outperform ‘research-grade’ instruments out of the box,” says JuLynn Ong, PhD, the first author of this work.

In their present form, lower-cost sleep trackers cannot be recommended for use by persons serious about tracking their sleep or for use by researchers. They may have a place as a physical reminder that sleep merits attention.

“Oura can be proud of the investment they made in developing and training their sleep algorithm with a large number of persons of different ages and ethnicities,” Chee says. “These objective results speak for themselves.”

Wondering if using your smartphone in bed interferes with your sleep tracking? Learn more about how in-bed smartphone use impacts the accuracy of your sleep tracker in this companion work by the same team.

RELATED: Oura Accuracy Further Validated by New Study from the University of Tokyo