An international research team recently published their study investigating whether or not Oura Ring could be used to help identify symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Traditional screening methods are limited in their scope and frequency,* whereas wearables like Oura have the power to enable qualitative data (e.g., mood questionnaires) to be paired with continuous physiological data (e.g., sleep patterns, heart activity, etc.), helping spot warning signs of mental health episodes or decline.

“Over 450 million people each year suffer from depression and anxiety — a number which, unfortunately, seems to be growing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Currently, 80% of those people go undetected or don’t receive appropriate treatment. That number is even higher in middle and low-income settings,” says Isaac Moshe, PhD Researcher at the University of Helsinki, who led the study. “Our research considers the most effective way to treat mental illness at scale.”

He continues, “This is especially important given the limited number of healthcare providers. We believe that digital biomarkers — unobtrusive signals from smartphone and wearable devices like Oura — could have a huge role to play in helping identify early warning signs associated with mental illness and thus enable more timely, personalized, and preventative interventions.”

Study Design

Researchers from multiple universities joined forces (University of Helsinki, Ulm University, University of Oulu, University of Freiburg, and Northwestern University) to recruit 60 participants, ages 24-68, to take part in the study for 31 consecutive days.

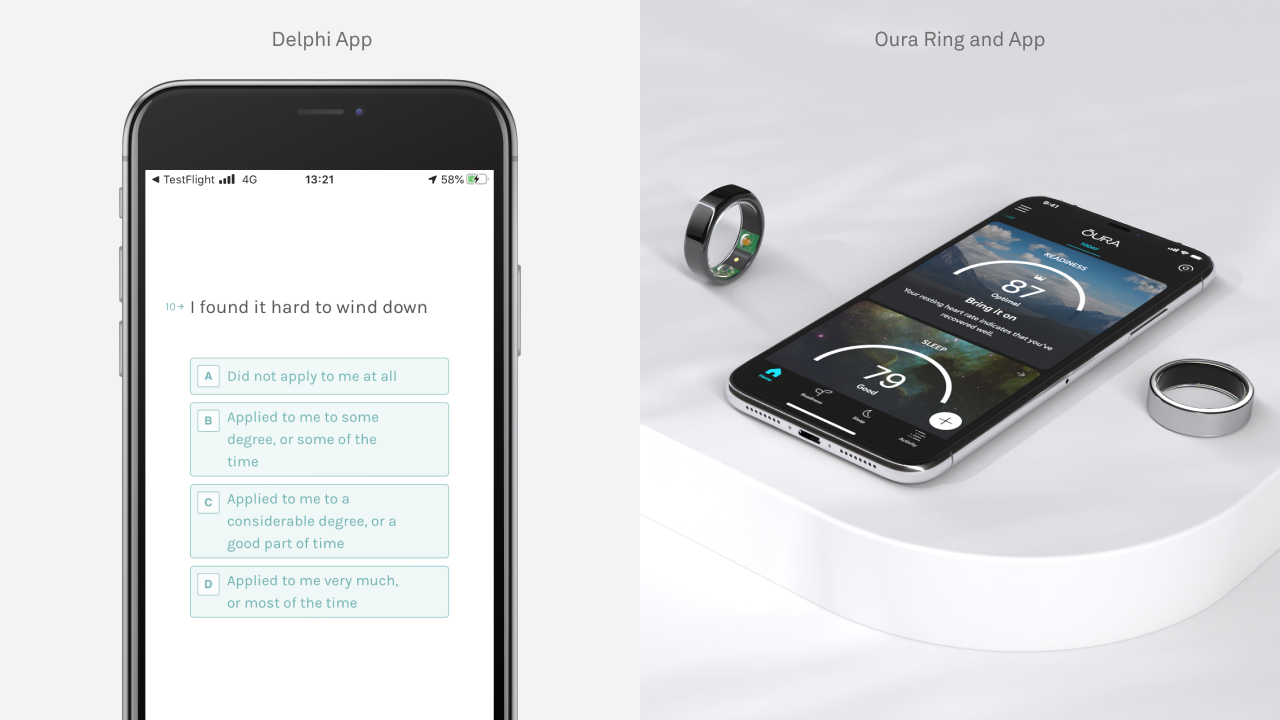

Participants downloaded an iPhone app called Delphi that continuously gathered the following data:

- Location: The Delphi app continuously monitored participants’ location using GPS

- Smartphone usage: The app reported total phone usage time and frequency of use

- Physiology: Oura Ring provided daily sleep, activity, and heart rate variability (HRV) data

- Self-Report: Participants filled out daily mood and self-report assessments of depression, anxiety, and stress

The Findings

The study was conducted during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, as governments across the world instated widespread restrictions. The researchers themselves noted the value of having wearable data during this unique period of restricted movement:

“Conducting the study during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic was really interesting for us. On the one hand, digital biomarkers have the potential to identify important insights on population-level mental health that may not otherwise be observed. On the other hand, you have very different underlying patterns around movement and mental health during COVID-19 and that is entirely different from data that has fueled previous studies in the field.”

The most notable patterns they uncovered were:

- Delphi Location: Participants who visited the same locations over and over showed more symptoms of depression, while those who had more variability showed fewer depressive symptoms.

- Oura sleep data: On average, the longer people spent in bed or sleeping, the higher their depression scores were. And, the more time they spent awake at night related to higher anxiety symptoms.

- Oura HRV data: They found a (surprising) significant positive association between HRV and anxiety: the higher the HRV the higher the anxiety on average.

The researchers ultimately found that a combination of smartphone and wearable data provided the strongest prediction of depression, highlighting the value of combining multiple data sources in predictive models.

These findings support previous research showing that individuals suffering from depression are often hit with fatigue and a lack of motivation, whereas individuals with anxiety often experience hyperarousal that may lead to more frequent and prolonged wake-ups after falling asleep. The researchers were additionally intrigued by their HRV data.

“Our counterintuitive finding that higher HRV was associated with higher self-reported anxiety really points to the need to conduct larger studies of this kind over longer periods of time.

We’re still exploring what factors may moderate the relationships between these digital biomarkers and mental health at the individual level. For example, a lot of the previous research on the association between HRV and anxiety has been in clinically diagnosed populations, whereas our study here was focused on a non-clinical population where the patterns may be different,” says Moshe.

READ MORE: HRV and Stress: What HRV Can Tell You About Your Mental Health

Participant-Driven Research

The Delphi Research Study was a unique form of participant-driven research where individuals who donated their data also received something in return. In this case, participants received a copy of their results with personal insights from a clinician.

Moshe notes, “When you’re doing this type of research, there’s a deep responsibility to give something back and to review the data properly. We took the time to prepare in-depth reports for each person participating in the study which were then each reviewed and commented on by a clinical psychologist before we shared them with the participants.”

One participant anonymously shares their experience:

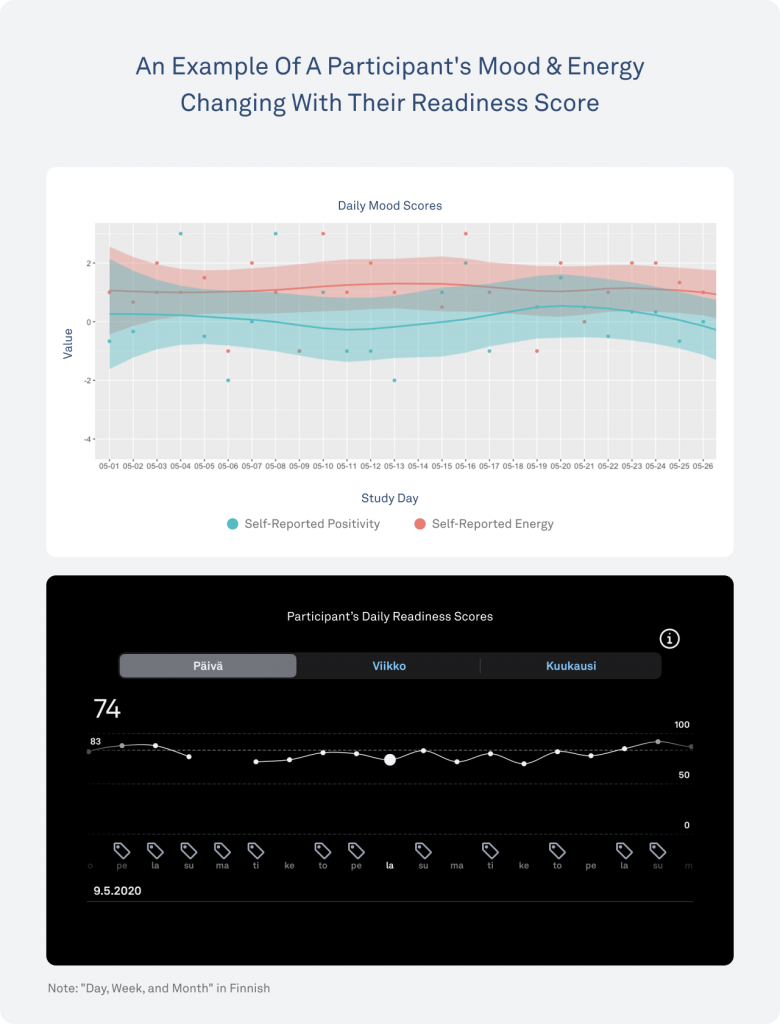

“Taking part in the Delphi Research Project in itself increased my self-awareness about how the pandemic affected my mood and general well-being. The study report revealed among other things, that my Oura Readiness Score related highly with my mood, and that in the evening I rate my positivity less than in the morning. These findings have helped me to make concrete changes such as increasing the frequency of doing yoga, having breaks during the day and meditating in the evenings. As a result, I have been able to cope with prolonged social distancing and have experienced an improvement in my physical and mental health.” — Anonymous Participant

Oura aims to support more participant-driven research in the future.

What’s Next?

“This was a great first study for us assessing the role of digital biomarkers in predicting symptoms of mental health and we learned a lot in the process,” says Moshe.

“Although a lot of our findings replicate what has been found in other studies, most of those studies have been conducted in the lab using lab-grade technology (polysomnography etc). As far as we are aware, this is the first study demonstrating that a validated consumer wearable device that measures sleep—i.e. Oura — can be used to predict symptoms of depression and anxiety, which is really promising.”

There is also a lot of evidence showing that insomnia is a precursor in the development of mental disorders. Wearable devices may provide a valuable way to identify these early warning signs and help individuals get help before it gets worse.

But exciting as that is, it’s important to remember that it is still early days here for both the field and for their own research.

Over the next year, Moshe and his team are planning to launch follow-up studies with larger sample sizes, over longer periods of time to explore additional signals to add to Delphi to improve the predictive power. Eventually, Moshe wants to be able to use that intelligence to inform personalized interventions that really improve mental health outcomes.

RELATED: Study Using Oura Data Finds Elevated Body Temperature Associated with Depressive Symptoms

Oura products and services are not medical devices, and are not intended to mitigate, prevent, treat, cure or diagnose any disease or condition. Oura’s insights are suggestions based upon your data, and shouldn’t be substituted for medical advice or prevent you from taking a holistic view on your overall health. If you have any concerns about your health, please consult your doctor

*Note: The traditional way of assessing a person’s mental health is via questionnaire data – either administered by a clinician or self-reported by the individual. However, these methods have a number of limitations. Most notably, they often take place sporadically, with long intervals between them, during which time the symptoms may change considerably. Moreover, as patients typically only meet with a clinician once the symptoms have already developed to a certain level of severity, they are limited in their ability to identify issues – and thus intervene to improve them – early on. Wearable devices like Oura, that are continuously gathering data related to a person’s physiological state (e.g. sleep patterns, heart rate, etc), have the power to identify the moment-by-moment risk factors and warning signs associated with mental health episodes or possible decline.