As global travel becomes a routine part of modern life, so too does the experience of jet lag.

Even though jet lag is a familiar nuisance for frequent flyers, “most research to date has relied on small samples or lab-based studies, leaving a gap in understanding of how travel affects everyday people in real-world settings,” says Dr. Raphael Vallat, study researcher and Staff Machine Learning Scientist at Oura.

A new collaborative study conducted by the Centre for Sleep and Cognition at the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (NUS Medicine) and Oura dives deeper.

Researchers—including Vallat, Dr. Adrian Willoughby, Dr. Ju Lynn Ong, and Oura Advisor Dr. Michael WL Chee—analyzed 1.5 million nights of sleep from over 57,000 de-identified Oura members and tracked how sleep patterns shifted before and after nearly 65,000 long-distance trips. They found that while sleep duration recovers quickly, sleep timing and sleep architecture can take significantly longer to realign with the new time zone.

In addition, traveling eastward was found to be the most disruptive to sleep patterns; it delayed sleep onset, caused fragmented rest, and decreased the amount of time spent in both deep and REM sleep.

Read the full study here.

Study Design

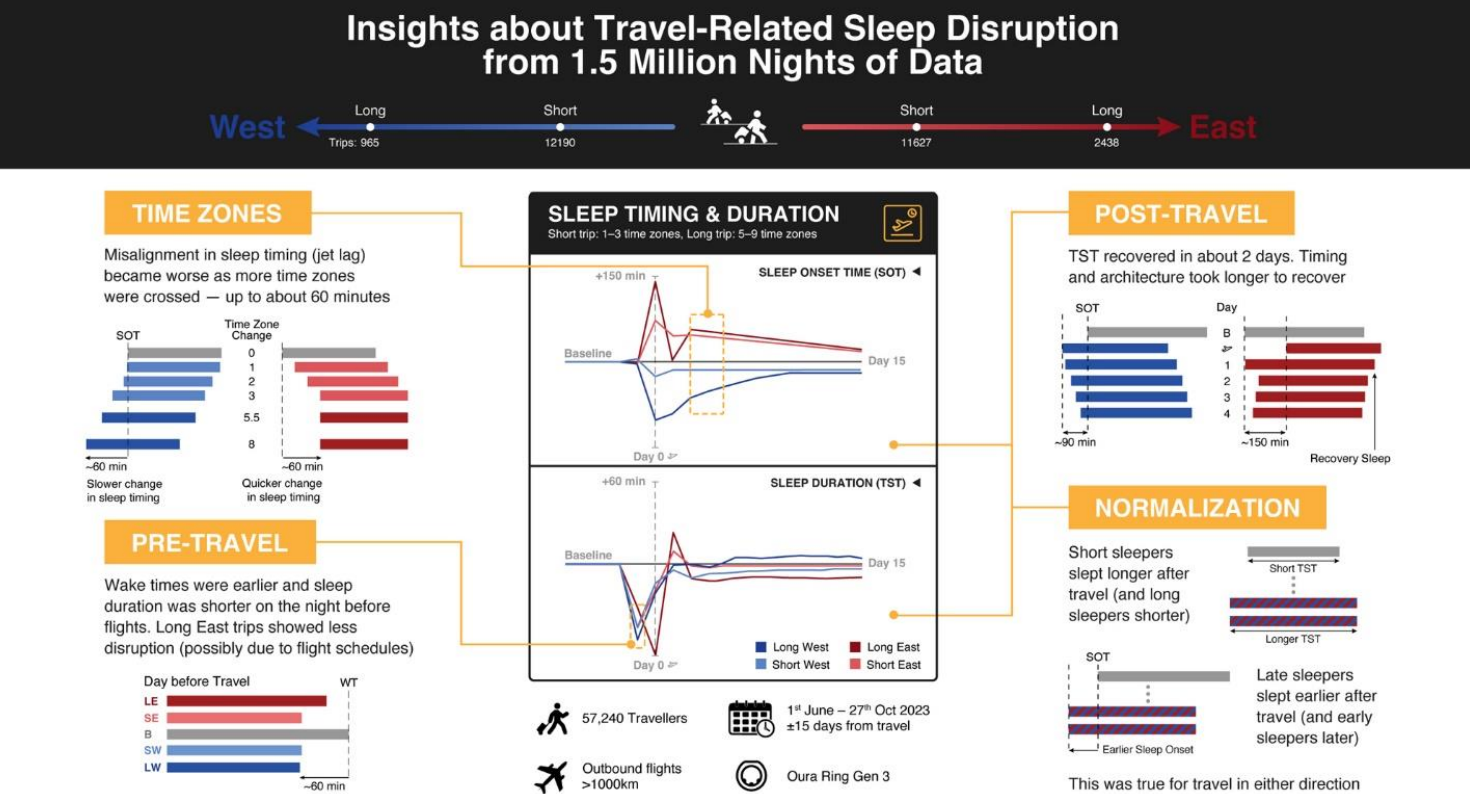

Researchers analyzed de-identified sleep data from 57,240 Oura Ring Gen3 members who took outbound trips over 1,000 km (621 miles), crossing one to nine time zones, between June and October 2023. Sleep was tracked for 15 days before and after each trip, totaling 31 days of data per person.

Using Oura Ring, researchers tracked sleep data, including sleep onset time, wake time, total sleep time, sleep onset latency, sleep efficiency, and sleep architecture (time spent in deep, light, REM sleep, and wake after sleep onset).

LEARN MORE: How Does the Oura Ring Track My Sleep?

Key factors examined included:

- Direction of travel (eastward vs. westward)

- Number of time zones crossed (categorized as one to three time zones as short trips and five to nine time zones as long trips)

- Changes in sleep duration, timing, and architecture (REM, deep, light sleep, and wake after sleep onset)

- Individual factors like age, sex, chronotype, and baseline sleep duration

Advanced statistical models were used to identify significant changes from the participants’ baseline sleep.

Key Findings

1. Sleep disruption starts before you fly.

- Sleep duration dropped by 30–50 minutes the night before travel, largely due to earlier-than-usual wake times—especially common for early flights.

- Later flight departures were associated with less sleep loss, especially for long eastward trips.

2. Sleep duration bounces back fast—but not sleep timing.

- Total sleep time recovered to within ~12 minutes of baseline by two days post-travel, regardless of distance.

- However, sleep timing (bedtime and wake time) remained misaligned even after 15 days, especially after long eastward trips.

3. Traveling east results in worse jet lag.

- Eastward travel led to later sleep and wake times, more pronounced circadian misalignment, and a greater drop in REM and deep sleep.

- Westward travel caused earlier sleep times and less severe disruptions in sleep architecture.

- Sleep architecture took up to a week to normalize after long eastward flights.

4. Sleep structure changes more than duration.

- On travel nights, REM sleep dropped, and wake after sleep onset increased, especially for long eastward trips.

- Even after duration recovered, travelers still had less restorative sleep—with more light sleep and less REM sleep and deep sleep for several nights.

5. Jet lag affects everyone, but individual traits matter.

- Younger people lost more sleep post-travel than older adults: 15 minutes more for a 20-year-old compared to a 60-year-old.

- Chronotype matters: Late sleepers struggled more to shift sleep times westward; early risers had more difficulty adjusting eastward.

READ MORE: How Your Sleep Needs Change Throughout Your Life

6. Travel reduces sleep disparities.

- People who usually slept less than 7.5 hours tended to sleep more while traveling, while longer sleepers slept less—a convergence of sleep duration and timing.

Key Takeaways: Navigating the Complexities of Travel Sleep

Although you may feel well-rested after a good night’s sleep following long-distance travel, this study’s findings indicate that your internal body clock may still be adjusting.

While the total number of hours you sleep will quickly realign with your body’s need for sleep, your internal circadian clock takes much longer to adjust to the new time zone.

“These findings can be used to develop practical strategies for minimizing the impact of travel on sleep and promoting better well-being,” says Dr. Vallat. “This study represents a significant advancement in our understanding of travel-related sleep disruption, providing a foundation for further studies.”

Advancing Sleep Research with Wearables

It’s important to note that wearable technology enabled these discoveries.

“This study demonstrates how wearables like Oura Ring have made it possible to analyze multi-night sleep data from travelers in real-world settings on a scale previously not possible,” says Dr. Vallat. “Providing researchers with an unprecedented wealth of objective, real-world data—offering invaluable insights that inform public health.”

Read the full study here.